The first universal language projects have their origin in the Cartesian idea that language should be universal and easy, based on the logic of reason. In their eyes, natural languages were logical and arbitrary creations, and they tried to structure a language which, based on the strictest logic, would be an instrument capable of becoming a useful tool for communication. The aim was to articulate a grammar so simple that it could be learned in five or six hours of study. Despite the effort, the words were very confusing and difficult to distinguish from one another.

These 17th century attempts were taken up again, with great force, in the 19th century, forgetting the rationalist approach to focus more on the linguistic aspects discovered in natural languages. As a curiosity, in 1852, Sotos Ochando, recovering the Cartesian approach, established a rational structure that had a certain force. For example: A, class of things; AB, material objects…; more curious is the solution of Translingua which tries to reduce the whole language to a succession of numbers, for example: 7131 means lion, since 7 designates the class of animals and 131 means feline, etc.

These systems, due to their artificiality, could not achieve the success expected of them, as they were rejected and did not allow easy communication.

As a consequence, the need arose to base the universal language on one or more natural languages. The first such attempt was the Volapük, an invention of the German priest J.IVI. Schleyer. He worked out a universal alphabet of 28 characters capable of transcribing all languages. The Volapük had a regular grammar of a certain complexity, the vocabulary was taken from natural languages and the words were greatly simplified, e.g. world > vol, speak > pük, animal > nim. It had a great development, many newspapers, magazines etc. were printed, but the lack of flexibility of its inventor to the possible evolution of the language led to the division and subsequent disappearance of this praiseworthy attempt.

One of the main lessons of the Volapük experience was the interest that universal languages aroused in the European bourgeoisie of the 19th century. The American Philharmonic Society in 1887 took up this interest, which was expressed in the following characteristics that a universal language should have a universal language should have:

Another of the causes that precipitated the decline of Volapuk was the appearance of the universal language that has become famous: Esperanto. This language was the work of a Polish oculist, L.L. Zamenhof, who in 1887 published a pamphlet in which he made his language known. Zamenhof’s ideal was the reconciliation of all people, and language was the main obstacle to this reconciliation.

It was therefore necessary to develop a neutral vehicle that would be accessible to all and would allow easy access to culture for all people.

Esperanto has produced a large number of translations and many original works, thus proving its suitability as a means of cultural transmission and creativity.

The 20th century saw a renewed interest in universal languages. In 1903 the Italian professor G. Peano created a new language directly inspired by Latin: Latino sine flexione, or Latin without declarations. Other attempts have included Interlingua, Ido, basic English…

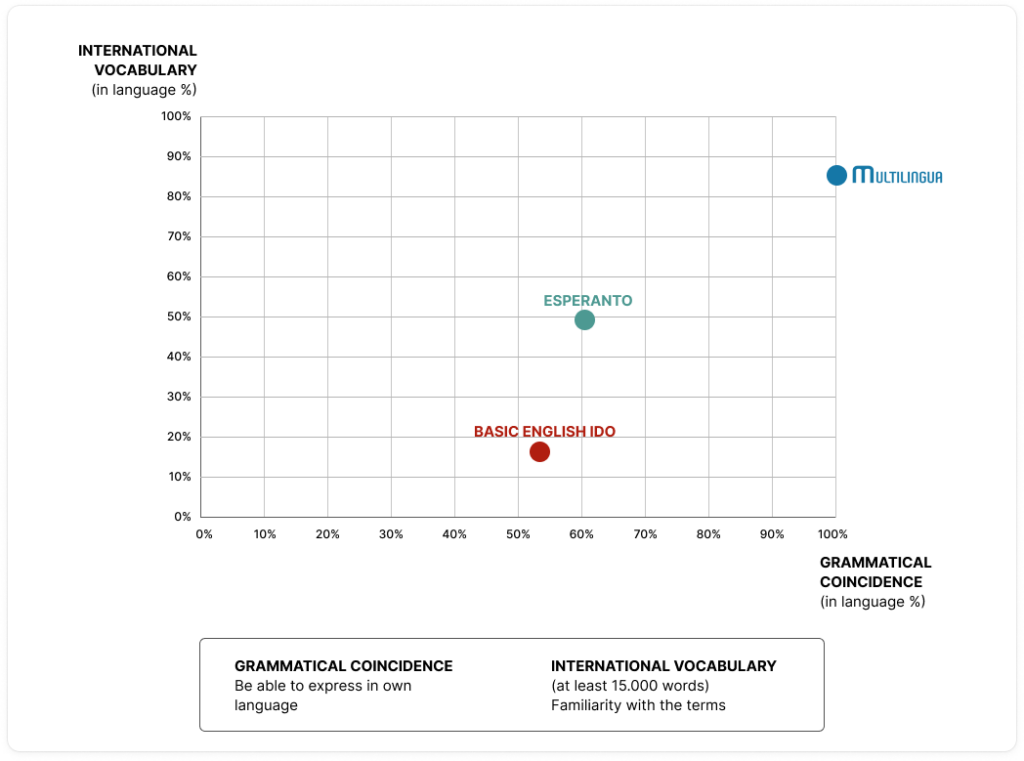

Of these attempts, the one that has made the greatest effort towards a universal language, and towards brotherhood among men, is Esperanto. The aim is to present a synthesis based on linguistic universals and an international Indo-European lexicon. A vehicle of communication which, on the basis of a very simple and flexible grammar, and a known or at least familiar vocabulary, is known or at least familiar vocabulary, allows people to communicate with each other: a universal bridge: MULTILINGUA.