Multilingua’s syntax is very simple, its main objective is to create a universal bridge of communication. A neutral, natural, flexible, simple and international bridge. It should be noted that the flexibility that characterises Multilingua allows it to be used by speakers of different languages without having to change its mental structure.

As for the syntax itself, it can be structured according to a series of recommendations, which are universally applicable in all languages of the world. It is much easier to understand any language than to write it, which is why it is important that Multilingua is very flexible so that it can be adapted to the fundamental structure of any language.

The basic sentence order, no matter how complex, in most languages has been understood by traditional grammars as reflecting the following scheme: subject, verb, object (S.V.O.). However, this scheme does not seem to clarify certain problems of universal grammar which make it difficult to establish it as a universal structure. It might be more convenient to replace this scheme by another one that allows us to understand, in a simpler way, the multiple linguistic structures of the world. A dynamic one that clearly explains the phases that languages have had in their development over time.

This scheme should be structured around two basic elements: PATIENT AGENT, theme commentary (understood in a different way from those of traditional grammar). These two elements could make it possible to explain in a simple way the complex structures that make up a language. One of the objectives of Multilingua would be to highlight the importance of this interactive complementarity between PATIENT AGENT and between the binomials subject-comment, subject-object, etc., which allows us to build on the simplicity of complexity.

This binary structure allows us to understand the more complex in a simple way.

It has to be taken into account that out of 5 billion inhabitants, more than 2.5 billion, i.e. more than half of them understand or speak Indo-European languages. Of the rest, Chinese, with more than 1 billion, also speaks a language whose order is S.V.O., according to traditional grammar; however, according to the above scheme, the ergativity of Chinese, among other problems, remains unexplained. If we opt for an explanation in which the AGENT-PATIENT structure is given priority, interactively complemented by the subject-comment (subject-object) binomial, these and other problems can be solved, as can be seen when we examine the place of the position of the verb, which will give rise to the functional structure or sentence.

In Multilingua, the order of the sentences is not rigid because although the A+V+P structure is recommended, thinking in any language in the world, any other structure can be used, thinking and writing with our own structure we can think and write in Multilingua.

We are going to look at the different linguistic structures of the languages from a general point of view, we are going to offer an overview of the different variations that are possible, as well as those supported by Multilingua.

The forms that exist in the world today, according to traditional grammar, are discussed below. (At some points it may not be very clear, and could be replaced by a table based on the categories of PATIENT AGENT, interactively complemented by the subject-commentary binomial (subject-object), which allows for a more coherent and simpler explanation.

S.V.O.

V.S.O.

S.O.V

There are also possibilities such as V.O.S., O.V.S. and O.S.V. (although this last structure does not occur in any language in the world in its usual form).

We must be aware that this division, proposed by traditional grammars, does not solve certain problems and also prevents us from understanding, in some way, the specificity of some languages. We should take into account what has been said above about the binomial PATIENT AGENT (basic structure) interactively complemented by the binomial subject-comment (subject-object).

The absence of the form O.S.V, in the traditional terminology, in which P A is proposed as correct, can be explained by understanding the following rules, which are observed in the relation Agent (subject) /Patient (object):

a.- the agent (subject), in language in its natural form, usually comes before the patient (object), the animate before the inanimate.

b.- the patient (object) in the language in its natural form, it is usually

is usually placed next to the verb.

This tendency confirms the possible theory that primitive languages would have this position, because it was more important WHAT was being done, TO WHOM it was being done, than who was doing it. The act was more important than the actor.

Before it was que, qui, (what, who]. What was important was the what and now it is the who.

As you can see the structure:

object + subject + verb, i.e.: P + A + V breaks the rules, which perhaps explains why it does not occur in any known language in the world.

What has been said so far can be seen in the following table, taking as a reference the terms of traditional grammar, which will be explained again using the binomial AGENT + PATIENT, complemented with the binomial subject-comment (subject-object)]].

S.V.O. S.O.V. S.V.V.

Le cat vise (a) le can = Le cat (a) le can vise

(English) (Basque)

V.S.O.V. V.O.S.

Vise le cat (a) le can = Vise a le cat le can

(Gaelic)

O.S.V. O.V.S.

A le can le cat vise = A le cat vise le can

(Does not exist in any language)

By putting a preposition before the object (O) “a” e.g. (Le cat vise a le

can), so that the order can be varied without losing clarity in the case of the complement of the noun or genitive.

These are the possible ways of writing the sentence in Multilingua, if the terms of traditional grammar are followed (as we shall see, the correct interpretation rests on the binomial AGENT + PATIENT). In all of them it has an understandable meaning, but not the correct one. In Spanish, many of them have meaning, since they may have been originally influenced by Basque, in which the change of order is habitual; a flexibility which is not admitted in English, French and other languages.

The minimum syntactic structure is composed of the following units: AGENT

PATIENT, together with the binomials subject-comment or (subject-object) interactively complemented.

In the same way that the most complicated mathematically has been reduced to the combination of O and 1, and the simplest computer is capable of solving complicated mathematical operations, syntax can and should be understood as the combination of two elements, which can be given different names according to the functions they are fulfilling. The terms presented below are used with a meaning that is not entirely equivalent to what is usually used in traditional grammars, although everything is reduced to the minimal structure: PATIENT AGENT, together with the subject-comment (subject-object) binomials complemented interactively.

In this study we will understand the following terms in a similar way, although we will not equate them: SUBJECT Subject central noun topic. COMMENTARY object object complement secondary predicate.

Although we will understand the PATIENT AGENT as a basic binomial and as interactive complements to: subject-commentary, subject-object…. That is to say, in all of them the relationship of complementarity that is established is the same as that between:

AGENT-PATIENT

Therefore, any fundamental linguistic structure, however complex it may be, can be reduced to these two essential components.

The structures we have examined above: determiner-determiner, subject-commentary, agent-patient, can undergo four primary variations which correspond to the following scheme:

A P

BASIC STRUCTURE

P A

This structure interactively complemented by the subject-commentary binomial (subject-object) develops the following variations, giving rise to the COMPLEMENTARY STRUCTURES.

tA cP ( sA oP )

Ac Pt ( As Po )

tP cA ( sP oA )

Pc At ( Ps Ao )

The lower case letters are the subject (t) and the comment (c), in other words the subject (s) and the object (o). Depending on their position, if they are placed before the sign defining the agent (A) or the patient (P), this means that we are normally dealing with a prepositional language, i.e. one that uses prepositions (Spanish, French, English). If they are after the subject, they are normally a postpositive language, i.e. they use postpositions (Basque, Japanese, Chinese). The change from a postpositive language, e.g. according to the complementary structure Ao Ps (in which the patient was not marked, in which the patient is the subject), when the agent takes on the function of subject, the postposition becomes the preposition of the patient, making them prepositional languages. With small indications, we can construct a table summarising all the possible structures that occur in the world, according to the following scheme:

| Fundamental Structure |

|---|

| sA oP tA cP |

| Ao Ps At Pc |

| sP oA tP cA |

| Pc As Pc At |

Starting from the binomial AGENT + PATIENT, together with the binomial subject-comment (subject-object) complemented interactively, doubled by position, and doubled by whether they are prepositive or postpositive in their way of marking the agent or the patient, they make a total of four variations. When the verbal function is added, it can occupy three different positions in each of the initial variants, making a total of twelve.

New complements can be added to provide more information, but redundancy should be avoided at all times and is only recommended if clarity is to be achieved. We must try to reduce the number of repeated elements in order to achieve economy of language.

In order to achieve the FUNDAMENTAL STRUCTURE, we must consider the role played by the receiver, who is a fundamental element in the sentence.

The fundamental structure is made up of: AGENT (ACTOR), PATIENT (OBJECT), INDIRECT PATIENT (RECEIVER), in addition they can be complemented by the PERSONAL AND LOCAL CERCUMSTANTIALS, which will be seen in the subject of the cases.

The sense structure can be of two kinds:

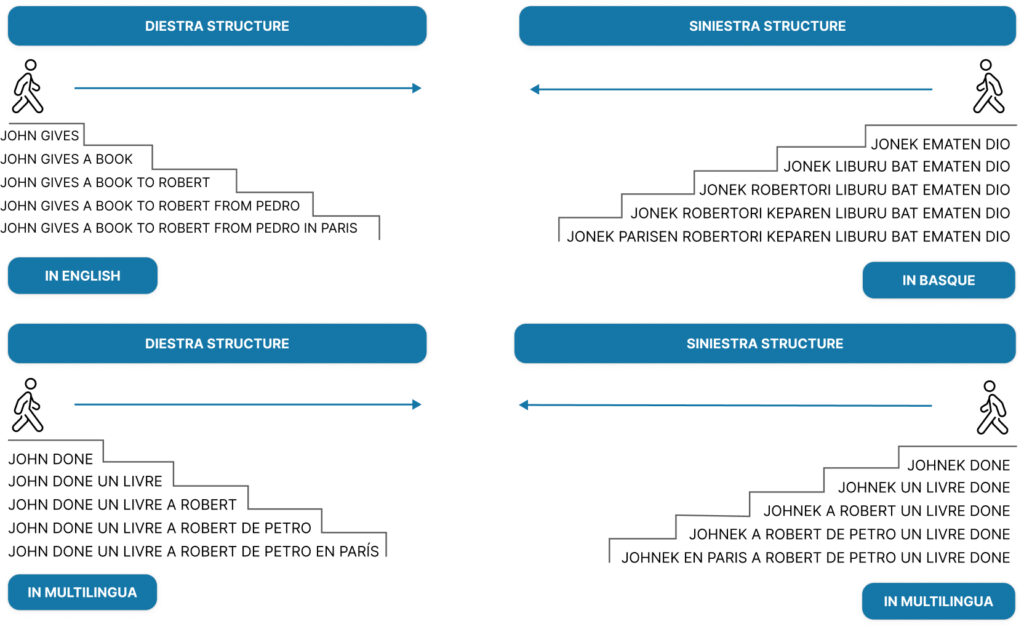

DIESTRA: COMMENTARY THEME -> diestra

SINIESTRA: COMMENTARY THEME <- siniestra

The above table can be explained as follows:

To these four basic structures we have to add the verb, which is sometimes the whole sentence, or what provides us with the most information.

The study of syntactic construction could have begun by taking the Verb as the nucleus and observing the evolution and functioning of languages when it is accompanied by the Patient and the Agent. That is to say, to consider the and its function as a fundamental element.

| Fundamental Structure |

|---|

sA oP |

Ao Ps |

sP oA |

Pc As |

+ V =

| Derivations |

|---|

| V sA oP sA V oP sA oP V |

| V Ao Ps Ao V Ps Ao Ps V |

| V sP oA sP V oA sP oA V |

| V Pc As Pc V As Pc As V |

In this next step we obtain twelve structures that allow us to understand all the languages of the world.

With this series of variations, the problem of ergativity can be understood, since what is marked as central, i.e. the theme (subject), is found in the Patient, in the determiner, which becomes determined by the agent. Although there is no definitive proof, it is not unreasonable to affirm that, at the beginning, ergative structures were dominant in the protohistoric languages of which we have news (even Indo-European itself, in its Hindi origin, was ergative, Hindi is ergative today, Latin was also ergative). However, the continued growth of transitive structures progressively influenced most ergative languages, which either lost their ergativity or drifted towards a mixed status that has confused many linguists who started from “purely” transitive premises.

Some structures of non-Indo-European languages, such as the case of the ergative of Japanese, Basque, Chinese, etc. can clearly explain some basic structures of other European languages, such as, for example, German, which in its main structure maintains a “Theme-commentary” order and in its subordinate structures alters this order, in theory German could be in an intermediate state of transformation between ergative and transitive languages, or the case of English with the Saxon genitive, which alters the normal English order and has a postposition instead of a preposition, due to the influence of Saxon.

This dichotomy should not be understood in a strict way, as there are only degrees of transitivity and ergativity between languages and even within languages.

To solve the problem of ergative languages Multilingua, bridge between languages, proposes to place a K after the Agent so that it is recognised as such by speakers of non-ergative languages.

Po As which, despite being unusual, also complies with the rules that have

which have made it possible to articulate the previous ones:

With these rules, it can be written almost literally in the different languages and understood perfectly. In other very different languages there are other nuances that are not relevant, but the general rules are valid.

In this way, part of the linguistic complexity can be understood in a less difficult way. We know that a lot of nuances can be left out along the way, however, because of its explanatory power and its simplicity, we opt for this reduction, which allows us to point out a possible explanation of the linguistic structure of most of the world’s languages.

From a more complex point of view, the different languages and their linguistic structures can be reduced and understood according to the position

adopted by the THEME:

Despite the extent to which the topic and commentary are graphically dimensioned, it does not correspond in normal language, but this graph is offered to facilitate the understanding of the complementary relationship between the topic and the commentary, and any extension of both the topic and the commentary is possible.

| DIESTRA CONSTRUCTIONS | SINIESTRA CONSTRUCTIONS |

|---|---|

| Topic-comment | Comment-topic |

| Determinate-determinant French Spanish English (latin) Russian Celtic | Determinant-determinate Basque German Japanese Chinese English (saxon) |

What has been said so far can be illustrated more clearly if we look at how the different languages express the genitive or complement of the noun, which in turn reflects the relationship of the basic binomial:

| DETERMINATE + DETERMINANT | |

|---|---|

| v.g. Legne porte | Porte de legne |

| French Spanish English (latin) Russian Celtic v.g. livre de papel | Basque German Japanese Chinese English (saxon) v.g. papel livre |

The order is first the complement and then the noun, but by adding the particle “de” it can be changed.

It is possible to put de legne porte, which would be a redundancy, but in Multilingua redundancies and concordance are not superfluous, even if they are not necessary. However, it should not be forgotten that one of the characteristics of all language is the economy it aims for. The aim should be to avoid the repetition of structures already present in the discourse without having undergone a significant variation which would allow them to be relevant again and to offer new information.

The basic order that has been offered so far: determiner-determiner, topic-comment, in which the former is the main target of communication and is the agent in most Indo-European languages. However, there are forms in which the central and important element of the sentence was not the agent but the patient. What mattered was what was being done, broken or otherwise, and not so much who was doing it. The what was more important than the who. However, perhaps because of the progressive alteration of customs, the “centre of gravity” of the sentence shifted from the patient to the agent. Consequently, the patient ceased to be the determiner and became the secondary element of the sentence, the determiner; the key position was occupied by the agent, which went from being determiner to determinate.

However, from a strictly linguistic point of view, the situation today is mixed. In general, there is more dominance of one construction over the other in each language, so it would be convenient to speak of degrees of dominance.

The following diagrams attempt to demonstrate the universal order adopted by the different structures:

The order ACTOR-OBJECT does not vary, what happens is that in one case the ACTOR is the subject and in the other the OBJECT.

ACTOR is the subject and in the other the OBJECT is the subject.

There is no such thing as a totally pure language in its structure.

Etxe gorri txiki polit a The beautiful little red house |

| DIESTRA STRUCTURE | |

|---|---|

| Topic-comment —————–> PLURAL+DEMOSTRAT.+ART.+ADJ.:AFECTIVO+EVALUAC+TAMAÑO+COLOR Comment – Topic <—————– | |

| SINIESTRA STRUCTURE | |