This section called Universal Grammar is based on Xabier Interideal’s documentation and notes, but there may be mistakes since it is an attempt to synthesise and summarise the Universal Grammar, so there may be mistakes.

The purpose of this essay (understood as an open proposal) is to show an attempt at universal grammar which is based on a series of basic ideas:

The most complex idea can be reduced to its basic components so that it is much easier to understand.

This intuition has had its most palpable development in mathematical logic, and in algebra, reducing the most complicated mathematics to the combination and hierarchical structuring of 0 and 1, that is to say, to a binary structure and the simplest computer is capable of solving complicated mathematical operations, even though in their construction and operation they are difficult for us to understand, reducing them, in their instructions, to their essential components, syntax can and should be understood as the combination of two elements, that is to say, of a linguistic binomial, which can receive different names according to the functions they are fulfilling.

We consider this essay, an open proposal, to be of great interest to people interested in automatic computer translation.

Specifically, in this essay we will use a composition method, which consists of:

This analysis, whose method is syntactic synthesis, is confronted with traditional grammar, which prefers to start from the whole (the sentence) to reach the parts (linguistic categories), establishing a decomposition or syntactic analysis.

These ideas are heirs to Cartesian analysis, which postulated that language should be universal and easy, based on the logic of reason. In our analysis, which is clearly based on computation, the role of semantics is not forgotten; although at the stage of knowledge in which we find ourselves it is difficult to assimilate, we, by virtue of the method, will leave its exposition and explanation, which must be brief due to the scant knowledge we have of its functioning and interactions with syntax, for the final part of this essay, without underestimating its importance, which is vital, as we will try to show.

The basic order of the sentence, regardless of the complexity, in most languages has been understood by traditional grammars as the reflection of the following scheme: subject, verb, object (S.V.O.) and their multiple combinations, e.g. (S.O.V) (O.V.S), etc. However, this scheme does not seem to clarify certain problems of universal grammar that make it difficult to implement as a universal structure. It might be more convenient to replace this scheme with another that allows us to understand, in a simpler way, the multiple linguistic structures of the world. A dynamic one that clearly explains the phases that languages have had in their temporal development.

This scheme should be structured around two basic elements: OBJECT VERB, comment-topic (understood in a different way than traditional grammar). These two elements could allow us to explain in a simple way the complex structures that make up a language. One of the objectives of a universal grammar, such as the one proposed by us, would be to highlight the importance of this interactive complementarity between the OBJECT VERB binomial and the topic comment, comment-topic binomial, which allows us to build complexity on simplicity.

This binary structure allows us to easily understand the most complex.

It must be taken into account that, of 5,000 million inhabitants, more than 2,500 million, that is, more than half, understand or speak Indo-European languages. Of the rest, the Chinese with more than 1,000 million also speak a language whose order is S.V.O., however, according to the previous scheme, the ergativity of Chinese would remain unexplained, among other problems. It must not be forgotten that more than three quarters of humanity speak ergative languages, that is, those in which what is done is more important than who does it. It must not be forgotten that the mother of Indo-European, Hindi, is ergative.

Although Chinese appears to respond to the S.V.O. structure, what actually happens responds to the scheme that we will see later, called mixed, A.C.V.O (Actor/Circumstances/Verb, Object).

If we opt for an explanation in which the OBJECT-VERB structure is given priority, interactively complemented by the theme-comment, comment-theme binomials, these and other problems can be solved, as can be seen when we examine the location of the actor’s position, which will give rise to the functional structure or sentence.

In our opinion, languages have followed the following pattern:

The forms that exist today in the world, according to traditional grammar, are discussed below. In some points it may not be very clear, and could be replaced by a table that is articulated around the categories of OBJECT-VERB, interactively complemented by the binomial comment-topic that allows a more coherent and simple explanation.

In this exposition, we will not yet speak of priorities or functions of the Actor or the Object-verb.

(S.V.O)

(V.S.O)

(S.O.V)

This classification poses many problems, e.g. Chinese and others, as we have said before.

Guaraní (Paraguay and Brazil) is a language whose main construction responds to a sinister structure: comment-topic.

Otomi (Mexico) is similar to Chinese, but evolved. It admits both the topic-comment structure (dextra structure), and the comment-topic structure (sinister structure).

The order of the ACTOR and the OBJECT is invariable, universal.

In addition, there are possibilities such as V.O.A., O.V.A. and O.A.V (although this last structure does not occur in any language in the world in its usual form). It should be noted that this division, proposed by traditional grammars, does not allow us to solve certain problems and also prevents us from understanding, in some way, the specificity of some languages. It should be taken into account what was said above about the OBJECT VERB binomial (basic structure) interactively complemented by the comment-topic binomial.

The absence of the O.A.V form can be explained if we understand the following rules, which are observed in the Actor/Object relationship:

This tendency confirms the possible theory that primitive languages gave priority to this position, because it was more important WHAT was done, over who did it. The act was more important than the actor (before it was what, who). What was important was the who and now it is the who.

The essential element is the action, the verb, and most of the inflections or valencies or alternatives are integrated into it.

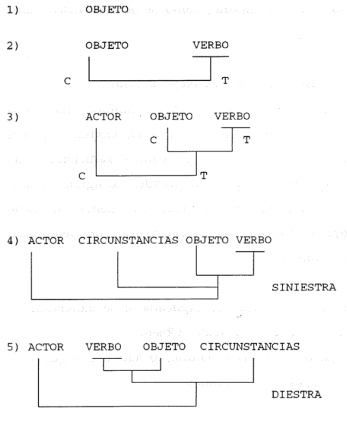

In the synthesis of the structure, the evolutionary order could be the following:

The important thing was the action, however, nowadays, for reasons of everyday life, the subject has gone from the object-verb to the actor.

The sentence was born from the object, e.g. food, water, etc., a series of objects to which the verb was later added, which they referred to as actions: food, eating, giving priority to the action of eating, over who ate, the later evolution added the Actor, but still giving priority to the action, it was in later times when the change to the situation in which we find ourselves today occurred, in a large part of the western languages, in which the Actor fundamentally prevails.

The change is great, since there is a change in structure from sinister to one of dexter, assuming a revolution in languages. Although there may be intermediate cases. To observe the transformation, see the table of universal order.

As you can see from the structure:

OBJET ACTOR VERB

that is:

O A V

breaks both rules, which perhaps explains why it does not occur in any known language in the world.

In short, we can say: in the beginning was the word and this was an object, although the first sentence was surely an interjection.

The minimum syntactic structure is composed of the following units: OBJECT-VERB, together with the binomials topic-comment, comment-topic complemented interactively.

Just as the most complicated mathematics can be reduced to the combination of O and 1, the simplest computer is capable of solving complicated mathematical operations, syntax can and should be understood as the combination of two elements, which can receive different names depending on the functions they are fulfilling. The terms presented below are used with a meaning that is not entirely equivalent to what they are usually used in traditional grammars, even though everything is reduced to the minimum structure: OBJECT VERB, together with the binomials topic-comment complemented interactively.

Therefore, any fundamental linguistic structure, however complex it may be, can be reduced to these two essential components: topic comment, comment topic.

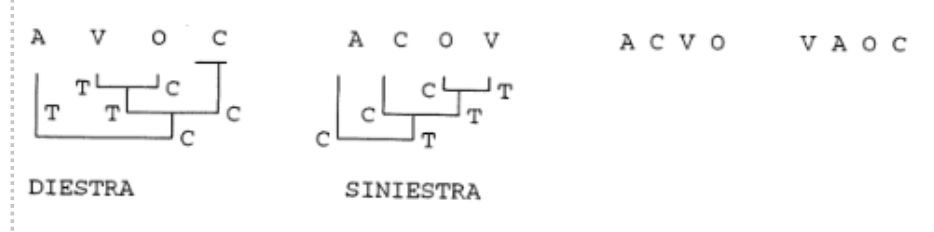

The structures we have examined above: determiner-determined, topic-comment, comment-topic, OBJECT-VERB, can undergo variations in a primary way that respond to the following scheme:

OV BASIC STRUCTURE

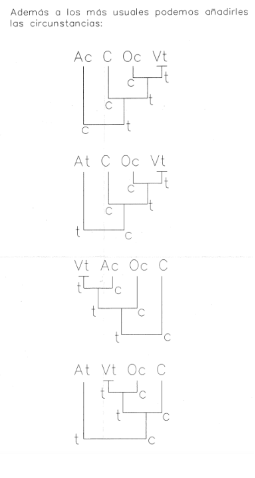

This structure interactively complemented with the binomial topic-comment, comment-topic, develops the following variations, giving rise to:

COMPLEMENTARY ESTRUCTURES

Oc Vt

Vt Oc

Lowercase letters are the topic (t) and the comment (c). Depending on their position, if they are placed before the sign that defines the VERB (V) or the OBJECT (O) it means that we are normally dealing with a prepositive language, that is, one that uses prepositions (Spanish, French, English). If they are after the topic, normally, it is a postpositive language, that is, one that uses postpositions (Latin, Japanese, Chinese, Basque).

With these small indications we can build a table that summarizes all the possible structures that occur in the world.

Starting from the OBJECT VERB binomial, together with the topic-comment, comment-topic binomials complemented interactively, duplicated by position, and duplicated by whether they are prepositive or postpositive in their way of marking the OBJECT and the VERB. When the ACTOR is added, it can occupy three different positions in each of the initial variants, in addition to varying in its consideration of TOPIC or COMMENTARY. The following table shows the different combinations:

VERBO TEMA

VERBO COMENTARIO

The structures we have examined above: determiner-determined, topic-comment, comment-topic, OBJECT-VERB, can undergo variations in a primary way that respond to the following scheme:

OV BASIC STRUCTURE

This structure interactively complemented with the binomial topic-comment, comment-topic, develops the following variations, giving rise to:

COMPLEMENTARY STRUCTURES

Oc Vt

Vt Oc

Lowercase letters are the topic (t) and the comment (c). Depending on their position, if they are placed before the sign that defines the VERB (V) or the OBJECT (O) it means that we are normally dealing with a prepositive language, that is, one that uses prepositions (Spanish, French, English). If they are after the topic, normally, it is a postpositive language, that is, one that uses postpositions (Latin, Japanese, Chinese, Basque).

With these small indications we can build a table that summarizes all the possible structures that occur in the world.

Starting from the OBJECT VERB binomial, together with the topic-comment, comment-topic binomials complemented interactively, duplicated by position, and duplicated by whether they are prepositive or postpositive in their way of marking the OBJECT and the VERB. When the ACTOR is added, it can occupy three different positions in each of the initial variants, in addition to varying in its consideration of TOPIC or COMMENTARY. The following table shows the different combinations:

With these rules, one could write almost literally in the various languages. In other languages there are other nuances that, because they are not exhaustive, we will not discuss here, but the general rules are similar.

In this way, one can understand part of the linguistic complexity in a less difficult way. We know that a great number of nuances can be left behind, however, due to its explanatory power and simplicity, this reduction is chosen, which allows us to point out a possible explanation of the linguistic structure of most of the world’s languages.

We can thus observe two cases of ergativity of sinister construction in English, which should not be forgotten as responding in its general construction to a structure of dexterity, e.g.:

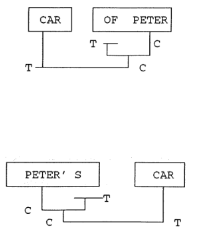

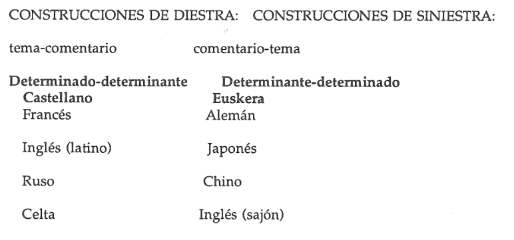

From a more complex point of view, the different languages and their linguistic structures can be reduced and understood according to the position adopted by the STEM:

DIESTRA / SINIESTRA (order)

DIESTRA: Car of Peter*

SINIESTRA: Peter’s car

(the examples are forced, as the natural tendency in the language changes)

This distinction can also be made in more complex structures:

In German, the main clause is usually dextra and the secondary clause is sinister.

What has been said so far can be illustrated more clearly if we observe how different languages express the genitive or complement of the noun, which in turn reflects the relationship of the basic binomial:

| DETERMINATE + DETERMINANT | |

|---|---|

| v.g. Libro de papel | Paperezko liburua |

| French Spanish English (latin) Russian | Basque German Japanese Chinese English (saxon) |

Diestra

Topic — Comment

Nominals

Noun — complement

Noun — adjective

Noun — relative

Noun — proposition

Verbal

Verb — adverb

Verb — object

Verb — circumstances

(Verb-object) — circumstances

Verbal nominals

Actor — verb

Actor — object

Actor — (verb-object)

Actor — [(verb-object)-circumstances]

Afixes (nexuses)

Preposition — noun

Determinant — noun

Prefix — noun

Negation — noun

Interrogation — noun

In summary, the construction of DIESTRA would be as follows:

English does not follow the adjective rule in the right-handed structure.

All of them use prepositions/affixes (prefixes).

Siniestra

Commentary — Theme

Nominals

Complement — Noun

Adjective — Noun

Relative — Noun

Proposition — Noun

Verbal

Adverb — Verb

Object — Verb

Circumstances — Verb

Circumstances — (object-verb)

Verbal nominals

Actor — verb

Actor — object

Actor — (object-verb)

Actor — [circumstances-(object-verb)]

Affixes (nexuses)

Noun — Postposition

Noun — Determiner

Noun — Suffix

Noun — Negation

Noun — Interrogation

In summary, the construction of SINISTER would be as follows:

All of them use postpositions and affixes (suffixes).

| DIESTRA STRUCTURE | |

|---|---|

| Topic-comment —————–> PLURAL+DEMOSTRAT.+ART.+ADJ.:AFECTIVE+EVALUAC+SIZE+COLOR Comment – Topic <—————– | |

| SINIESTRA STRUCTURE | |

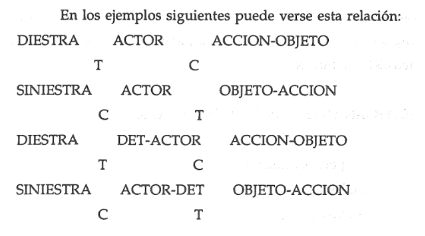

The ACTOR-OBJECT order does not vary, what happens is that in one case the actor is the topic and the object is the comment, in another the object is the topic.

These universal rules reflect the natural order, although in most cases they are not absolutely all fulfilled, because in all of them there is a mixed situation, there are certain mixtures, in most of them there are structures of diestra and of siniestra.

The basic order that has been offered until now: determinant-determinant, topic-comment, in which the first is the main object of communication is the ACTOR, the animated object, in most Indo-European languages. However, there are forms in which the central and important element of the sentence was not the ACTOR but the OBJECT. What mattered was what was done, broken or any other action, not so much who did it. What mattered more was the what than the who. However, perhaps due to the progressive change in customs, the “center of gravity” of the sentence shifted from the OBJECT to the ACTOR. As a result, the object-verb (verb phrase) stopped being the determinant and became the secondary element of the sentence, the determinant; the key position was occupied by the actor (nominal phrase) who went from being the determinant.

However, from a strictly linguistic point of view, the situation is now mixed. In general, there is more dominance of one construction over the other in each language, so it would be convenient to speak of degrees of predominance.

With all this we have arrived at what we properly call FUNDAMENTAL STRUCTURES:

The previous schemes correspond to the most usual ones, with others occurring as seen before.

The elements of the sentence are: actor action object circumstances. For this reason we must speak of: actors of the action, objects of the action and circumstances of the action.

DIESTRA: THEME – COMMENTARY

ACTOR, QUALITY OF THE ACTOR ———–> THEMATIC STRUCTURE

ACTION, QUALITY OF THE ACTION, MAIN OBJECT, FINAL OBJECT, CIRCUMSTANCES ———–> COMMENTARY STRUCTURE

SINIESTRA: COMMENTARY – THEME

QUALITY OF THE ACTOR, ACTOR ———–> COMMENTARY STRUCTURE

CIRCUMSTANCES, FINAL OBJECT, MAIN OBJECT, QUALITY OF THE ACTION, ACTION ———–> THEMATIC STRUCTURE

However, with this fundamental structure we have only explained what is generally understood as simple sentences, leaving aside the coordinated and subordinate sentences.

To explain them, it is necessary to intervene in the relationship between simple structures through postposition, preposition and conjunction.

POSTPOSITION:

(Joins words or sets of words of the same syntactic nature) Elements that relate (link) the nouns with the main element (actor or object).

CONJUNCTION:

(Joins words or sets of words of a different syntactic nature). The conjunction relates the propositions in a compound sentence.

Taking into account the above, we can observe that these compound sentences will always be structured in two sentences: a main one and a secondary one, the latter becoming the commentary of the first one.

Furthermore, we must not forget that for us the subordinate clauses perform the function of the linguistic category that they represent. Thus, for example, an adverbial subordinate clause performs the function of an adverb and can be analyzed as such, an adjective subordinate clause, that of an adjective, and so on.

Now is the time, once we know the interaction of the three elements of our linguistic triangle:

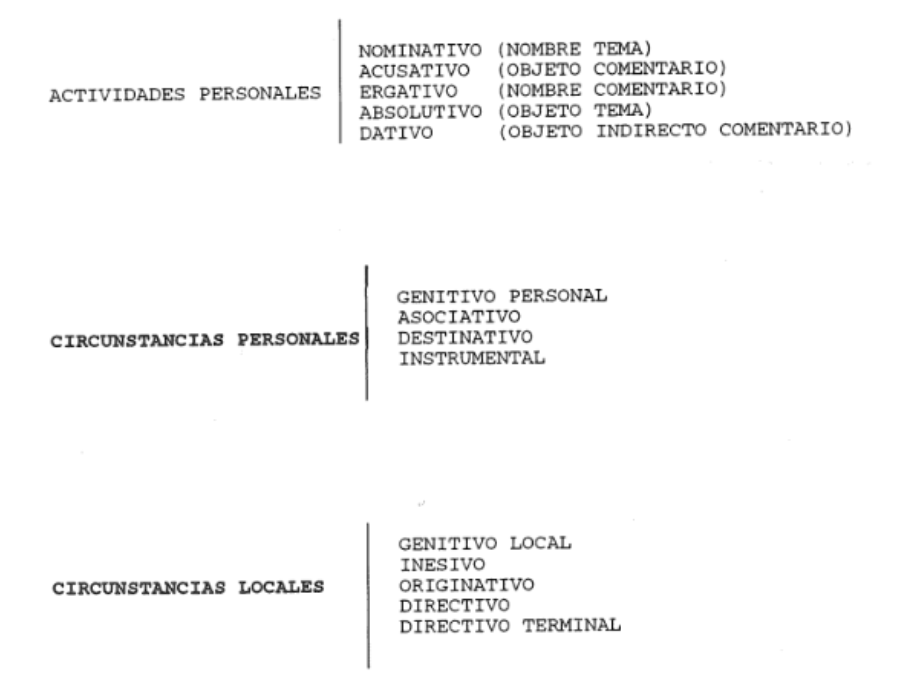

Let us move on to the explanation of the roles that the different categories used up to now can play. Specifically, the actor, the object and the circumstances (which we will divide into personal circumstances and situational or local circumstances).

This distinction between personal circumstances and local or situational circumstances is not only found in what has generally been understood as cases or declensions, but is also observed in the verb. Thus, for example, a distinction is often made in the Basque verb between EDUKI and UKAN.

This distinction can be misinterpreted if one is not aware that in the case of the verb UKAN we are not referring to a personal possession and in the case of the verb EDUKI to a local possession. Although usage can distort these tendencies.

The same occurs in the case of Spanish, with the dichotomy: SER-ESTAR, or HABER-TENER.

In the case of the verbs: Ser, Haber, we are faced with personal circumstances, and in the case of Estar and Tener, with local circumstances.

A paradigmatic case of all this is the case of Japanese, which, by placing two different particles before it, can, with the same sentence, determine which circumstance it is referring to, e.g.

“The sky is blue”, “sora wa aoi desu” (sky/definite) blue / is, precedes the particle wa (definite, personal circumstance).

“The sky is blue”/”sora ga aoi desu” (sky/definite) blue / is, precedes the particle ga (indeterminate, local circumstance)

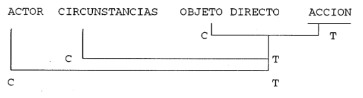

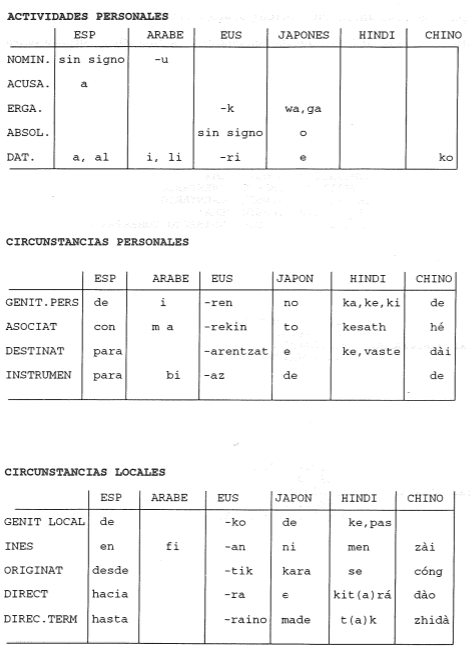

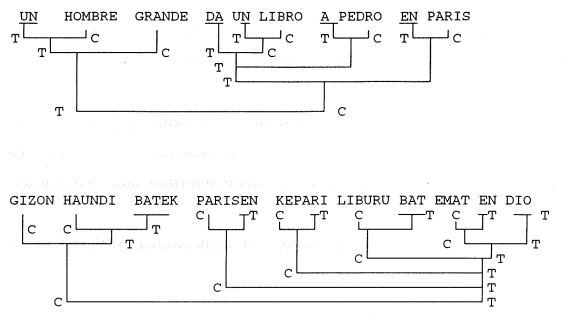

An application of all that has been said can be seen in the following syntactic synthesis:

This same analysis may vary depending on the context where it is performed.

FULL WORDS

What we have seen so far corroborates our starting point and analysis:

One of the most important keys to universal grammar is that it is binomial.

The main theme is that there is a binomial order of the right (dextra: topic comment) and another of the left (sinister: comment topic). This binomial is present from the simplest and most elementary structure to the most complex: the sentence (even in compound sentences).

And on the other hand, within languages there are a series of levels:

FORMAL: the form

ORDINAL: the order of the right or left

STRUCTURAL: the binomial comment topic, topic comment

But this binomial structure does not only occur at the level of syntactic structure, but it occurs even within what is generally understood by linguistic categories: noun, adjective, adverb, verb, and all their classes and derivations.

Those that are normally understood as linguistic categories can be redefined, following a binomial scheme, in a way that allows us to exchange them, according to the valency or inflection that mainly determines them.

Thus:

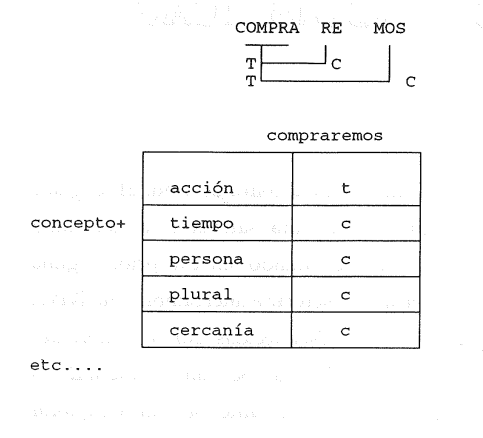

As we have said before, this is their principal valency or inflection, since they have others, which are the ones that give them all their specifications. In the case of the verb, e.g.:

Concept + Action + Time + Aspect … = VERB

Without intending to be exhaustive, the list of valencies or linguistic functions would be:

CONTEXT

All of them can be presented in different degrees and states. Thus, for example, temporality: present, past, future, habitual, perfect, imperfect, etc.… gender: masculine, feminine, neuter, in some African languages there can be more than seven genders.

That is why we prefer to talk about full words, since any word or linguistic category, however insignificant it may seem, provides a great deal of information, e.g., the particle “te” can provide us with a great deal of information if we analyze it rigorously. Thus, “te” tells us that it is “a tu”, that is, it contains a local possession, it is dative, close, singular, etc…

Its table of valencies would be:

concept +

te

| dative case: a | t |

| person: second | c |

| gender: depending on the context | c |

| number: singular | c |

Mine could be broken down into “I of” a full word “mine” is composed of “I” existence, personal, gender, number, and “of” personal genitive, together “mine” would be like in the case of the Japanese “I of”, that is, a personal genitive, existence, gender, number, person, said in two words.

In all linguistic categories this analysis can be established, reaching a decomposition in which one of the valencies, or inflections or functions, acquires the main character and the others a secondary character, reappearing again the classic binomial, theme-comment.

Generally each linguistic category is usually characterized by a determined valency, and a series of secondary ones, which establish a hierarchy of comments.

Thus, for example:

concept +

existence = noun

quality = adjective

action = verb

mode = adverb

That is, a noun is the dynamic interaction of a concept and the valence of existence (which acts as a comment) and multiple comments (the other valences that may or may not be present).

For example: house, has an existence, a number, gender, determination, animation, finitude, etc. All of this can be represented in the following way:

concept +

house

| existence | T |

| person | C |

| number | C |

| gender | C |

| animation | C |

In a given context, the hierarchy of comments will be different than in another context, where the number or the concreteness or the determination may be more important, and even in particular cases there may be two themes or even the main valency may become secondary, becoming a comment.

As for the verb, it can have infinite valencies or inflections that characterize it, although its main valency is the action.

However, now we are interested in highlighting two: the case and the aspect.

As for the aspect, it tells us if an action is being carried out (Imperfective aspect) or has already been carried out (Perfective aspect).

As for the case, it will help us to distinguish within this valency a series of degrees (do not forget that in all valencies there can be infinite degrees). Specifically, in the verb, we can talk about four, depending on the actors of the action:

Once this interaction between the basic binomial: topic-comment and the linguistic categories and their valencies is known, we can explain the linguistic functions, briefly, and how they are carried out by means of these categories by virtue of their main valency.

A verb can be subject to the following analysis:

The basic and main function of a language is communication. Language is the tool that human beings use to satisfy the imperative need to communicate. All languages in the world, without exception, articulate a communication system that allows messages to be specified and exchanged. Although the diversity of the multiple solutions established by the different languages may seem otherwise, this is not the case. The different functions that every language fulfills will be described and, therefore, rules that are taken for granted, but which are rarely reflected upon, will be explored. For example, if we say: “MAN”

The word MAN is undetermined, MAN is an abstract concept.

In spite of everything, if we make its category table we would see how full of information it is. All of this within a certain context.

concept +

man

| existence | topic |

| gender | comment |

| number | comment |

| gender | comment |

| concretion | comment |

| animation | comment |

In one context the topic would be gender, in another it would be an animated object, etc. In a historical context, when referring to the man of the 16th century he would not have gender, etc.

If you want to move from abstraction to a message you have to use concrete references, that is, individual markers that make the abstract concept MAN unique, e.g. THE man.

You have already moved from the first abstraction to an already identified entity that, logically, needs further markers that identify it even more: that relate it to us, that qualify it, that quantify it until you achieve, if you wish, a complete determination.

If you say “men” you get a first determination (in the hierarchy of comments, the number occupies the main place). A higher degree of determination is achieved if you add an identifier “the men”. The next degree is obtained with a quantifier “the three men”.

Other languages will do it differently, but they will always have to have: identification, relationship, etc.

IDENTIFICATION (THE ARTICLE)

All languages in the world identify the actor and the object around which messages and communication are articulated. For example, in Spanish the articles, both definite and indefinite: a man, men. The distinction between the two is marked by the degree of identification.

The article is the mark that, placed before the noun, serves to indicate whether the object designated by it is known or not. Its main value is identification and according to the degree of identification it provides we can classify them as definite or indefinite.

THE RELATION (ADJETIVES DEMOSTRATIVES, PERSONALS AND POSESIVES)

Just as all languages in one way or another have to identify the elements of communicative discourse, they also have to relate them. That is, show the place they occupy in said discourse. This relationship can be demonstrative, personal of existence, personal possessive, local personal.

The demonstrative relation places an element in relation to the proximity or distance it occupies, that is, it specifies or limits the meaning or extension of the noun by establishing a spatial relation.

This function, carried out with the demonstrative adjective, although it is carried out in a different way in different languages, all have in common the establishment of the spatial dimension, commonly in two or three degrees:

We see how in the table of valencies of the demonstrative adjective the main comment is the spatial location, the quality that the adjective tries to show is a spatial quality.

concept +

adjetive demostrative

| existence | comment |

| quality | topic |

| gender | comment |

| localization | comment |

We see that in this case the main comment is the valence of the location, which can easily become the topic.

The personal possessive relation, as a function of the relation, connects the elements of the discourse with the subjects or persons, indicating their relation of ownership with respect to the person who speaks, the person who listens, or a third person who is spoken of. This function, in all languages, is carried out by the possessive adjective.

The adjective refers to a quality of the name it accompanies, determining and qualifying it (e.g. beautiful mountain), or adding a precise meaning to a name (e.g. snowy mountain), or indicating a number or expressing an order (e.g. two mountains) and a succession. The possessive adjective refers to the quality of ownership with respect to the persons involved in the communication.

As a curiosity, in Chinese, the possessive is made with the postposition “of”, curiously the same as in European languages where it is a preposition. In Japanese, the locative possessive is also the postposition “of”, but not the personal one.

In Chinese, wo de shu (I/of/book) = my book.

Wo péngyoo de shu (I/friend/of/book) = my friend’s book.

In Japanese, watashi no hon (I/of/book) = my book.

THE CUALIFICATION (DELICATIVE ADJETIVES)

If I say dog, we are referring to an animal. If I say black dog, I am referring to a dog of precisely this colour. The word black is a qualifying adjective that in some way specifies or limits the meaning of the noun dog.

This function of determination is carried out by means of the subfunction of qualification, which consists of giving a relevant property to the discourse, that is, it adds qualities (e.g. white dog). It is usually done by means of the qualifying adjective, which attributes properties that limit or specify the elements that are the protagonists of the communication, its main value is the qualification.

Generally, we usually talk about nominal qualification (e.g. big house, fast horse) and propositional qualification (e.g. the house that is on the mountain is Peter’s) but this study will be limited to the nominal qualification, because both fulfill, in different ways, the same function and following our basic rule, the explanation of complexity by simplicity, we have to explain only the one that expresses the content of this function in a clearer way, the nominal qualification.

In the nominal qualification, the most normal thing is to put the adjective before the noun, e.g. in Chinese, English, German, Russian. In classical Arabic, however, the adjective is placed after the noun. In French, Spanish the normal order is after, although it can change by altering the meaning (e.g. an old friend is different from an old friend).

Three degrees of meaning of the adjective can be distinguished: positive, when it expresses a quality (red); comparative, when it expresses the degree of this quality in relation to a second term (more red), and when it expresses quality in an extreme degree (very red).

THE QUALIFICATION (PLURALS, QUANTIFIERS)

The purpose of this function is to indicate the number of things or entities taking part or referred to in the discourse, i.e. to indicate whether a word refers to a single idea, person or thing, or to several.

This function can be carried out in two ways, with the plural or by adding quantifiers, which are elements that are added to the noun to indicate quantity.

It is different if you say la casa, which refers to a single house.

If, on the other hand, you want to express several things or ideas, you use the plural or quantifiers: las casas or dos casas. In this case the main valency would be the number.

As for the quantifiers, special words that determine the plural, a clear distinction can be made: those languages that need the quantifier and the plural, such as English, Spanish, and those languages that do not need to add the plural, e.g. Hungarian, and classical Arabic, as well as Basque (etxe bi = two houses; the noun is in the singular, while in Spanish the noun is necessarily in the plural).

Quantification cannot be done in the same way with all entities, for example, you cannot say two waters or two wines, unless you confuse the container with the content and you are referring to a glass of water, etc. In English this is clearly expressed by the distinction between countable and uncountable.

So far, we have seen several linguistic functions that are common to all the languages of the world, and which are realised using different solutions that are close to each other.

All the functions described in this chapter serve the same purpose, they determine the structure of the discourse by means of almost common mechanisms, they place a series of marks which:

ASSIGNMENT (SIGNALLING)

We have seen how the different languages determine: with identification, relation, qualification and quantification. Now it must be examined how further information is provided in the discourse. For example: this radio.

You have already determined in a concrete way which radio you are referring to, however, if you say: this radio is in front of me, you have assigned a quality or characteristic to the radio, you can already distinguish it more easily from other radios: because you have assigned it a location, a place in space, it is in front of me.

Its valence table would be as follows:

concept +

| location | t |

| gender | c |

| existence | c |

| number | c |

It can also vary depending on the context.

This linguistic function is assignment, which consists of predicating, saying, affirming, something about objects already determined previously in the linguistic structure.

This man is in front of the house, a specific man is being located, assigning him an existence. If we also say THIS MAN IS IN FRONT OF MY BIG HOUSE, a new assignment is being added to the previous assignments, which consists of attributing a quality to him (which is big).

This function, assignment, has a series of subfunctions: location, possession, existence and attribution.

Generally, location is carried out by means of adverbs of place: the books are on the shelf.

The books referred to have been located by assigning them a place, by means of the adverb of place. Its main valence is location, that is, concept+action+place.

POSSESSION (PERSONAL AND LOCAL)

An important distinction in the function of possession is that which must be made between personal and local possession. In this sense, the case of Basque is particularly illustrative, since different verbs are used to emphasize this distinction, which cause initial confusion among students, e.g. For the case:

personal: belarri bi ditut

local: bi kapela dauzkat

In personal possession, when we say kapela dut it refers to my hat with a very personal nuance, however, when we say kapela daukat we refer to a hat that may not be mine, with a more local (situational) nuance. Of course, usage can vary this tendency of the language.

PARTICIPATION (ACTIVITY)

NOMINATIVITY AND ERGATIVITY

The next function is participation, which establishes the inclusion, or activity in the action to which the discourse or linguistic structure refers, as well as the way of acting of the different elements and their characteristics within it. In a language it is very important to indicate who or what the actor is.

And also to indicate in what relation he is in relation to the others, since if this is vague or confusing the communication is seriously compromised. Since it is not the same to say: Juan gives to Pedro than Pedro gives to Juan.

Its two main subfunctions are:

a.- Nominative voice

Generally, the transitivity and intransitivity of the verb are usually remembered as two radically opposed and exclusive concepts when studying grammar according to traditional precepts. However, they have not been considered opposites or mutually exclusive for some time now. The current conception places more emphasis on degrees of transitivity and intransitivity.

The nominative voice includes both transitivity and intransitivity because, despite the classic distinctions, the former depends on the element to which they are related and which they determine. Thus, the greatest transitivity will occur when, in the structure, a person with respect to an element determines it in such a way that it changes it in a noticeable way. This change can be both local and temporary, such as affecting its own structure.

On the other hand, that is, in the intransitivity, the person or element that carries out the main part of the action (be it an animal, a thing or other beings) does not modify, create or determine the object in a noticeable way, since it does not change its structure or its state, whether in a temporary or local way. However, at the extreme of less transitivity, when a verb structure without an object is established, it can be observed that this type of modification does not occur.

Although this distinction has nuances, e.g. there are transitive verbs that can function intransitively and vice versa.

b.- Ergative voice

The next subfunction is the ergative voice, which has been commonly misinterpreted due to an underestimation of the importance of ergativity with respect to nominativity. The classical interpretation considered ergativity as a “less evolved” state linguistically than nominativity. Undoubtedly, ergative languages are older and gave greater importance to what was done to who did it, the Action Object over the Actor, and today greater importance is given to the Actor than to the Action Object. The misinterpretation was based on the fact that ergative languages are less known than nominative languages. The latter focused the attention of linguists, who were speakers of nominative languages and applied their schemes to the study of all languages.

In the Nominative voice the Actor is not marked, the nominative is not marked, the accusative and the dative are marked. In short, the identification or mark of the nominative is that it is not marked, or by its position.

If we take an example from Euskara, to compare the degrees of transitivity:

Mikel Bilbon egongo da (Miguel will be in Bilbao)

Mikelek janaria egingo du (Miguel will make the meal)

Although it seems that there is a distinction, if we examine it more closely we can see that the important thing is to establish the syntactic position, that is, to know if we are faced with a Comment Topic construction, or a Topic Comment to avoid confusion. For years linguists have drawn a line of division between ergative-absolutive and nominative-accusative languages.

The lack of transitivity that occurs in ergatives is due to the fact that the subject is in the object-verb and not in the actor. This is the case of Japanese, which does not have a subject, it is clear that it does not need one.

In some languages, both structures exist, e.g. Hindi, Nepalese, Georgian…. Furthermore, the most important thing is that a language can be syntactically or semantically ergative without being morphologically so (that is, without having the endings that mark ergativity, this appearing in a “veiled” way).

THE RELATIONSHIP

This linguistic function is responsible for establishing a relationship between the people who are involved in the communication with the circumstances in which it occurs. It is of great importance since if it is not known in an effective way to whom it is being referred, at what time or in what place it is, or in the context, then the communication would be seriously compromised, and could become ineffective.

In order to relate the discourse with the people, the personal relation is used, thereby ensuring knowledge of the people involved, as well as their role within it, in the same way to communicate the place where the structure is carried out, the local relation is used, finally to indicate the time in which the communication takes place, the temporal relation is used. As can be seen, the clear explanation of these three functions is a priority objective of any linguistic structure, since if they are not carried out properly, it is very inefficient. In addition to all these, in fact, there are: aspect, etc…

These functions use a series of markers that in the case of the personal relation are the personal pronouns, in addition to the personal inflection of the verb. The local relation uses the demonstrative pronouns and adjectives. Finally, the temporal relation uses temporal adverbs and verbal conjugation.

In the personal relation, the first surprise is the diversity of people that are found when studying the personal pronouns. This diversity is not such, since it can be reduced to two basic elements or at most three, specifically the minimum units would be “you” and “I”. To denote a third person in Spanish “he”, it is saying that it is an existing and distant person. The other persons are nothing more than possible combinations of these three elements.

Its table of valencies would be:

concept +

he

| location | t |

| person | c |

| existence | c |

In the local (situational) relationship, what is intended to be marked are places and their relationship with respect to the subject who is carrying out the structure. Therefore, depending on who the reference pole is, one or another marker is used, in this case the demonstrative pronouns and adjectives, which indicate the proximity or distance with respect to the protagonist.

In the temporal relationship, an attempt is made to establish a connection between the protagonist of the action and the time in which said action occurs; in short, an attempt is made to mark the temporal development of the discourse.

RELEVANCE OR VERIFICATION

Relevance or verification is the function that is responsible for connecting the discourse with prior knowledge. It connects something that is already known with the contributions that can be received through a new linguistic communication and thus obtain more information. If these two parts were disconnected, no type of information would be received, or it would be erroneous if this new information is not supported by something known to us that is not pertinent or verified and will mean nothing to us, e.g. If you don’t know anything about algebra and you are presented with a simple equation like “x+1 =3” you will be unable to understand it, much less solve it.

Something similar happens in languages, since you can understand the language or the linguistic code, but not certain messages. On the other hand, nmnfgjkvgj may not mean anything, but it may make sense in the given context in which this combination has a previously established meaning, that is, it is decodable, and therefore relevant in said communicative circumstances. Similarly, if the information received is not connected to previous knowledge, no new information will be received. Thus, for example, if you are not trained in a field of research and you receive specialized information, you will be able to recognize the sounds and even reproduce them, but you will not understand what is meant.

In a much more familiar context, if at the beginning of a conversation the interlocutor names us John, a common name, without other indications, references or determinations, we will not know which John he is referring to. To get out of the confusion, we are forced to ask him which John he is referring to, that is, to determine, assign, relate that John to the topic of the previous conversation.

There are, therefore, two elements in the communication process

These elements can be called topic and comment, respectively.

The comment is the part that indicates what is new that the discourse brings, however, this is not entirely true, the novelty arises from the interaction between the two elements, the topic and the comment. One without the other would not be able to structure a pertinent (coherent) communication. E.g. If in a conversation the interlocutor is told that John has given a book and he knows which John the message refers to, John would be the topic and he has given a book would be the comment. The comment has given provides new information only if it interacts with the topic. In other words, the comment has given would only provide very little information, it needs the topic, prior knowledge, to be relevant.

The realization of relevance is possible through the following methods:

The first three, and others less important, belong to what we could call finite relevance, because they are limited, easily identifiable and definable.

The context, on the contrary, belongs to what we could call infinite belonging, because it is unlimited, difficult to identify, and indefinable, it is impossible to know its limits.

NEGATION

If you ask a question when you use a structure, you must note that what you are doing is not saying that what is said in the comment is not related to the information contained in the topic. If you say Los hombres no son altos, you are saying that height is a property that cannot be applied to said men.

This negation can be done in various ways: by means of a negative verb, by means of a negative particle (Spanish: Yo no veo), or by adding an auxiliary particle (as in the case of English: I do not see; and French: Je ne vois pas).

IDENTIFICATION

This identification is carried out by means of interrogation, which can be of two types:

The absolute interrogation affects the whole sentence and is carried out, in different languages, by means of intonation or the order of the words or by means of particles. English and Spanish use the change of order (Lidia se ha casado- Se ha casado Lidia?; and in English: Lidia has married- Has Lidia married?), Chinese normally uses the particle “ma “. Basque uses both methods, on the one hand it uses the position of the words and on the other it uses the particle “al”.

The relative interrogation is used to highlight the element of the structure that is to be highlighted. This indication is generally made with interrogative pronouns.

HIGHLIGHTING

It is interesting to note that, in addition to the negation of the comment and the interrogation, highlighting techniques can be used, which allow you to mark in a specific way what you want to highlight. In this way, a word or part of a sentence can be highlighted (emphasized) without establishing changes in the structure. There are languages that, by highlighting, change the structure of the sentence.

CONTEXT

As we have said before, context belongs to what we could call infinite belonging, because it is unlimited, also difficult to identify and indefinable (it is impossible to know its limits).

When we say the word “LOVE”, depending on the context in which we find ourselves, e.g. in a personal context: mother and daughter, friend-girlfriend, spouses, friend-friend, friend-girlfriend, acting interactively with other contexts, such as, for example, in a romantic situation, or in a place: the bed, or in a time, or a bell, a tone, etc. it can have multiple different meanings.

Context, among its infinite characteristics, has the particularity of varying with the history of each person.

This also happens, of course, with concrete words, such as chair, which have a different meaning in different people, situations, places, times, etc.

A sentence with a form (the words), an order (the order of right or left) and a structure (the binomial theme-comment, comment-theme, etc.), in different contexts has different meanings.

One can imagine a prism with a base of an equilateral triangle, in which at each of its respective vertices is the formal, ordinal, structural, and at its height the infinite contexts that this triangle can have, forming the linguistic prism. This can be transformed into an algebraic structure of an independent variable and infinite dependent variables.

Contexts can be infinite: PERSONAL, TEMPORAL, SITUATIONAL (place, time, history, personal relationship, experiences, memories, etc.)

There will never be two identical contexts, because the time, people, place, circumstances, environment, experiences, tone, timbre, etc. may have changed. Even the most trivial aspect can change the meaning of a sentence.

Heraclitus’s sentence “No one can bathe in the same river” has a real application here.

That is why the context is the valence that makes the other valences adopt a position in the hierarchy of comments or even usurp the place of the subject, at a given time.

Despite everything, as communication is necessary, we must establish a universal bridge, which can allow us to communicate, even being aware of the limitations imposed by the impossibility of defining the multiple contexts that interact in a sentence. This universal bridge could be the embodiment of a language according to the rules of universal grammar.